Simple Acts of Stream Stewardship

Simple Acts of Stream Stewardship

By Rebecca O’Hearn, MDC Stream Team Supervisor

Hello Stream Teamers! My name is Rebecca O’Hearn and I started working for the Stream Team Program in August. These first few months in the Program have been amazing! I’ve had the pleasure of meeting some dedicated and passionate individuals who donate their free time to keeping our streams and Missouri beautiful. I’ve also been so lucky to join a work team who not only has this same level of passion, but also has an equally impressive level of talent. You all are truly an inspiration!

I’m new to the Stream Team Program, but I’m not new to conservation and environmental work. For the past 13 years I served as the Missouri Department of Conservation’s Pollution Biologist. I am grateful for what was an eye-opening 13 years. My days were filled with spills, kills, and ills. That is, spills of pollutants that killed fish and wildlife, and concerns about declining aquatic life and funny-looking water and fish. I was shocked to learn in my first year in that role that water pollution and die-offs of aquatic critters occur on a regular basis in Missouri.

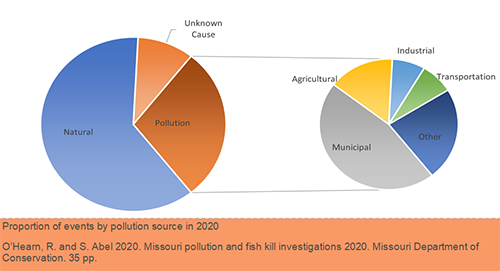

Every year, the state handles on average 100 of these events. Half of these events are caused by extreme environmental conditions like drought, heat, and cold spells. The other half are caused by pollution, chlorinated drinking water, or pollution spills that pose a threat to, or outright kill fish and wildlife. Pollutants vary widely, from acid spills to fertilizer spills. One of the most unexpected pollutants I encountered was milk. That’s right, milk! A truck carrying a load of milk overturned, spilling thousands of gallons into a small stream. Within a matter of hours, microbes started breaking down the milk, a process that used all the oxygen in that part of the stream which suffocated gilled animals, including fish.

Now, milk was an unusual pollutant. State records dating back to the 1940s show the leading pollutants over time have been from municipal sources. Municipal pollutants include wastewater, chlorinated water, and power facilities. Wastewater and chlorinated water are finding their way into streams through broken pipes, manhole overflows, and potable water runoff from residential areas.

Can we do anything to stop these events from happening? Yes!

There are many simple acts we can do as Stream Teamers to fix this problem. The first being education — we can educate our friends, family, neighbors, and classmates. Most Missourians are unaware of these issues and may not realize that simple everyday behaviors contribute to the problem.

Some other simple acts of stream stewardship include:

- Throw disposable wipes, feminine products, and grease in the trash. Flushing these products or pouring them down the drain contributes to manhole overflows.

- Wash your car at the car wash so the runoff is routed to a wastewater treatment plant instead of the small stream in your neighborhood.

- Skip watering the lawn after a rainy day; and stop watering if you notice water running off into the road or your driveway. The runoff water contains chlorine which will kill gilled organisms once it reaches your neighborhood stream.

- Let the pool sit untreated for several days before draining it at the end of the swimming season.

- When possible, use non-salt and non-chemical alternatives to remove snow and ice on driveways and sidewalks. If salt treatments are needed, use them sparingly to avoid turning your freshwater stream into a salty one that will harm freshwater critters.

And lastly, one important step we can all take is to report any odd colors, odors, and dead animals in and around water to the state. The state has a team of professionals trained to investigate these events and coordinate the clean-up of pollutants. To report, call the Missouri Department of Natural Resources Environmental Emergency Response (573-634-2436).

As we move further into the winter months and are spending more time indoors, know that our streams and the critters in them still need protection. Keeping a watchful eye on your local stream goes a long way!

Top: Private pond, Audrain County, 5/12/20. Bluegill with a bacterial infection, photo by landowner.

Bottom-Left: Mississippi River, Scott County, 9/8/20. Fish kill in a backwater caused by low dissolved oxygen from receding flood waters, photo by John West (MDC - Scientist).

Bottom-Right: Tributary to Cold Water Creek, St. Genevieve County, 4/28/20. Large mats of diatoms, photo by Jason Crites (MDC - Fisheries Management Biologist).

Farewell, Kat Lackman

Farewell, Kat Lackman

“He used to often say there was only one Road; that it was like a great river: its springs were at every doorstep, and every path was its tributary.” – J.R.R. Tolkien

As I find myself navigating the river of life it has come to a confluence bringing change and the realization that the tributary I was on has led me to a new and bigger path. As of September 1st, I no longer served as a Stream Team Coordinator but have accepted a new position within the Missouri Department of Conservation as the new Public Use Data Coordinator.

This is an opportunity to expand myself, that despite my love for this great Program, that I could not pass up. As many of you know I tended to be the one behind the scenes keeping many of the Program’s day-to-day functions like the website and data entry forms up and running, as well as being the “numbers” person for compiling reporting numbers to highlight the awesome things you all have accomplished. These duties along with a commitment to data integrity and standardization have primed me for taking my knowledge to a bigger scale in assisting with standardizing department-wide data resources.

functions like the website and data entry forms up and running, as well as being the “numbers” person for compiling reporting numbers to highlight the awesome things you all have accomplished. These duties along with a commitment to data integrity and standardization have primed me for taking my knowledge to a bigger scale in assisting with standardizing department-wide data resources.

To say that this change is bittersweet is an understatement! I have been with the Stream Team Program for more than 14 years and the position of Coordinator is what I consider the start of my professional career. I have met and befriended so many passionate Stream Teamers, staff, and volunteers alike; thinking about stepping away was a very difficult decision. But I am confident the river will flow on and all the outstanding people out there that make this Program great will continue to shine as the best stream stewardship program in the nation.

As said by many before me, it is never goodbye but until we meet again, and I am sure our rivers will cross again. Until then, I will SYOTR (See You on the River)!

Wild Waterway Rescue Challenge

Many thanks to everyone who participated in the inaugural Wild Waterway Rescue Challenge! This event featured the opportunity to support your favorite zoo in Missouri — Kansas City, Saint Louis, or Dickerson Park Zoo — while keeping our waterways clean at the same time. Over the weekend of November 5-6, a total of 117 participants removed more than six tons of trash from their adopted streams in the name of aquatic and wildlife habitat protection. Among the three zoos, participants collected the most trash in support of the Saint Louis Zoo, which will claim the trophy for the 2022 challenge. Top participants for each zoo with the highest trash totals from the weekend also win a $100 adopt-an-animal sponsorship.

Many thanks to everyone who participated in the inaugural Wild Waterway Rescue Challenge! This event featured the opportunity to support your favorite zoo in Missouri — Kansas City, Saint Louis, or Dickerson Park Zoo — while keeping our waterways clean at the same time. Over the weekend of November 5-6, a total of 117 participants removed more than six tons of trash from their adopted streams in the name of aquatic and wildlife habitat protection. Among the three zoos, participants collected the most trash in support of the Saint Louis Zoo, which will claim the trophy for the 2022 challenge. Top participants for each zoo with the highest trash totals from the weekend also win a $100 adopt-an-animal sponsorship.

Congratulations to this year’s winners:

- Ashley Johnson, Stream Team 6030, for Dickerson Park Zoo

- Dean LaBoube, Stream Team 1920, for Kansas City Zoo

- Bernie Arnold, Stream Team 211, for Saint Louis Zoo

Stay tuned for the next challenge this coming fall!

New Nitrate Kit!

By Tabitha Gatts, DNR Volunteer Water Quality Monitoring Coordinator

Hello Stream Teamers! If you haven’t heard already, we have a NEW nitrate kit with our Volunteer Water Quality Monitoring Program! The LaMotte Tablet Kit is different than the old kit in that it uses tablets added to a sample to test for nitrate rather than a mixed-acid solution and a cadmium-reduction powder. We’re very excited to start using this kit because it is much safer for the user and for processing/handling the waste. With this new kit you can containerize the waste, take it home, and pour it down the drain. Prior to this, volunteers had to deliver their nitrate waste to an MDC or DNR facility for treatment before disposal. The ranges of values that this kit measures are a bit different than the old one. The new kit does not have specific ranges below 1.0 mg/L like the old kit did, but instead measures 0 - 1.0 mg/L as its own range, up to 15.0 mg/L N03-N. Using these new ranges will still help identify if nitrates pose a nutrient concern in your stream. If you are entering data for nitrates into our online database, simply enter the reagents from the new kit as if they were the reagents from the old kit. The names of these new reagents will be updated once we establish a new database.

Hello Stream Teamers! If you haven’t heard already, we have a NEW nitrate kit with our Volunteer Water Quality Monitoring Program! The LaMotte Tablet Kit is different than the old kit in that it uses tablets added to a sample to test for nitrate rather than a mixed-acid solution and a cadmium-reduction powder. We’re very excited to start using this kit because it is much safer for the user and for processing/handling the waste. With this new kit you can containerize the waste, take it home, and pour it down the drain. Prior to this, volunteers had to deliver their nitrate waste to an MDC or DNR facility for treatment before disposal. The ranges of values that this kit measures are a bit different than the old one. The new kit does not have specific ranges below 1.0 mg/L like the old kit did, but instead measures 0 - 1.0 mg/L as its own range, up to 15.0 mg/L N03-N. Using these new ranges will still help identify if nitrates pose a nutrient concern in your stream. If you are entering data for nitrates into our online database, simply enter the reagents from the new kit as if they were the reagents from the old kit. The names of these new reagents will be updated once we establish a new database.

The purpose of measuring nitrate or nutrients in general in a stream is to gather information on nutrients that might be impacting algal growth and other plant production in the stream. Excess algal growth can cause algal blooms that in turn may negatively impact dissolved oxygen (DO) levels and consequentially aquatic life. Low levels of nitrates are natural in streams. If you’re seeing higher levels of nitrates in your stream consistently (above 2.0 mg/L or 10.0 mg/L if near a point source)—you may want to check for sources of nutrients in your watershed. Some sources might include run off from parks/streets/lawns that contain animal waste or fertilizers, discharges from wastewater treatment facilities, and poor functioning septic systems. Missouri does not have water quality standards for nitrogen or phosphorus, except that 10.0 mg/L of nitrate is the maximum for water bodies that are drinking water sources. Citizens can help mitigate nutrient input by picking up after their pets, following instructions when fertilizing lawns/fields, and performing best management practices with plant or animal farming to reduce runoff into nearby waterbodies.

Since our last issue of Channels, Stream Team members reported:

- 855 total activities

- 5,874 total participants

- 16,954 hours

- 30.6 tons of trash collected

- 211 water quality monitoring trips

- 10,295 trees planted

Check out more highlights below . . .

Team 1790 – A few guests joined Team 1790 for a Father’s Day water quality monitoring event on Bonhomme Creek. “This was their first time seeing the ‘bugs’ in the creek,” said Dustin Hills.

Team 2760 – Deer Creek is now 13 bags of trash and several large items lighter, thanks to Team 2760’s efforts!

Team 2760 – Deer Creek is now 13 bags of trash and several large items lighter, thanks to Team 2760’s efforts!

Team 2800 – Forty-nine zoology students from Smith-Cotton Sr. High, Sedalia (Team 2800), participated in an educational monitoring event at Big Buffalo Creek Conservation Area. The students had spent the week prior to the event learning to identify macro-invertebrates so were very excited to use their new knowledge in the field.

Team 2800 – Forty-nine zoology students from Smith-Cotton Sr. High, Sedalia (Team 2800), participated in an educational monitoring event at Big Buffalo Creek Conservation Area. The students had spent the week prior to the event learning to identify macro-invertebrates so were very excited to use their new knowledge in the field.

Teams 4264 – Team 4264 worked with Riverfront Campground and floated from NRO to Riverfront's first takeout on the Niangua River. Picked up 5 tires 2 wheels. The haul came out to 15 green trash bags and 10 red mesh bags, plus several tires, a paddle, fishing poles, and a metal frame for a picnic table. Nice work!

Teams 4264 – Team 4264 worked with Riverfront Campground and floated from NRO to Riverfront's first takeout on the Niangua River. Picked up 5 tires 2 wheels. The haul came out to 15 green trash bags and 10 red mesh bags, plus several tires, a paddle, fishing poles, and a metal frame for a picnic table. Nice work!

Join AmeriCorps through Stream Teams United

Join AmeriCorps through Stream Teams United

Stream Teams United has been serving as a sponsor of an AmeriCorps project since 2019, and the project is still going strong! This past summer, ten AmeriCorps members served at Stream Team sites around the state of Missouri, with each member building capacity of education and volunteer efforts at each host site. As a project sponsor, Stream Teams United partners with Stream Team sites to place members to serve at the site in either 12-month or summer positions.

Current participating host sites include Watershed Committee of the Ozarks, the James River Basin Partnership, Missouri River Relief, the St. Louis Aquarium Foundation, Open Space Council, Maramec Spring Park, Northeast Community Action Corporation, and Howardville Community Betterment. AmeriCorps members at host sites have been helping to build water quality education curriculum, grow native plant programs, recruit volunteers for green space restoration projects, and build partnerships to connect more youth to nature in their service area.

AmeriCorps service opportunities can be a great way for graduating students to get a year of experience with non-profit organizations, build their network, and learn new skills. AmeriCorps positions are also a great way for people of any age to serve their community and receive a modest living stipend and end-of-service monetary award. There are currently openings at several sites throughout the state. Starting dates for 2023 are flexible at various sites and include the following possible dates: February 13, March 13, April 10, May 8, June 5, June 20, July 17, July 31, August 14, and August 28. Summer-only positions may also be available.

The application period is open at several sites. You can find out more about the Stream Teams United AmeriCorps project at https://www.streamteamsunited.org/americorps.html and learn more about the benefits provided to AmeriCorps members in the VISTA (Volunteers in Service to America) Program at https://americorps.gov/members-volunteers/vista/benefits. If you know of anyone who may be interested in joining the Stream Team AmeriCorps program in 2023, please reach out to them and share this opportunity!

Workshop Highlight: Plywood Canoe Building

Workshop Highlight: Plywood Canoe Building

By Brian Waldrop, MDC St. Louis Stream Team Community Education Assistant

It has been a long time coming for this Canoe Building Workshop. The behind-the-scenes planning for this workshop started back in the fall of 2019. Then, as you all are aware, Covid-19 hit, ending all workshops as we knew them to be. Flash forward 2.5 years, and the Canoe Building Workshop was back on and, for the first time, held in the St. Louis Region.

Participants from Missouri and Illinois attended the workshop held at Paddle Stop in New Haven, the ideal place to have this class and a picturesque venue overlooking the Missouri River.

Ted Haviland, the legend and master craftsman (Team 674 - Scenic Rivers Stream Team Association), was the instructor. He planned to build two canoes and raffle off one to a participant. Starting late Friday afternoon, former National Park Service’s Dave Tobey and Ted began to cut and prep for the weekend’s class. Saturday morning, twelve attendees and Ted were in full swing cutting, clamping, and gluing pieces together before adding the fiberglass and epoxy. The building of these canoes was true teamwork.

Inside and outside temperatures slowed the pace, so it was time to explore Old Town New Haven. Astral Glass and the Missouri River pleased their idle hands, all while Paddle Stop Brewery served breakfast and lunch. Once the epoxy set, they all were back at it, sanding, filling, and shaping the vessel. As day one ended, the canoes would rest until day two.

Bright and early on Sunday, the canoe builders were back at it. It was time to attach the gunwales and bow decking before adding more epoxy. Four sheets of plywood were starting to look like two river-worthy canoes.

“I never knew woodworking could be so much fun,” said Rejoice O’Morgan, while Nicole Landwehr stated, “It was an incredible weekend of learning, building canoes, and building friendships.” You could see the anticipation on the faces of the builders who would be walking away from this workshop with a canoe. The canoes’ final touches were applied just before adding another coat of epoxy.

As the epoxy set, Shane Camden, the owner of Paddle Stop, was called in to draw the winner of the canoe. Twenty-six hands built the boats with null to advanced skill levels, and Dave Tobey was the lucky winner to paddle away with the canoe.

Simple Acts of Stream Stewardship

Farewell, Kat Lackman

Wild Waterway Rescue Challenge

Monitoring Minute

Team Snapshots

Coalition Corner

Workshop Highlight

Winter 2023